New England Stone Walls – Icon at Risk

TIME

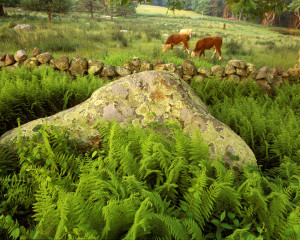

This photograph is about 4 billion years of foreplay by fire and ice.

It’s about bedrock forged in fiery tempests 300 million years ago.

And about mud and sludge beneath the Iapetos Ocean

transformed into the gorgeous banded rocks

visible all over New England today.

It’s about England and New England parting company

200 million years ago when Pangea suffered the ultimate rift,

leaving five miles of sedimentary rock.

It’s about 2 million years of intense glaciations

leading up to the final ice age 20-30,000 years ago

when the Laurentide Ice Sheet roared down from central Canada,

scouring bedrock, splitting rock,

and dragging these rocks to this pasture.

It’s about 11 generations of Stonington farmers who cleared this field,

piled stone upon stone to keep pastures open for grazing livestock.

Maybe 250 or 300 years of caretaking at this one spot.

It’s about f32 at ¼ second, the infinite space

between this blink and that blink.

As much as lighthouses, covered bridges, and grist mills, stone walls are signature icons of New England. Today, they stand in peril, challenged by developers who subdivide the landscape and disrupt the historical timeline of our early agricultural past.

As much as lighthouses, covered bridges, and grist mills, stone walls are signature icons of New England. Today, they stand in peril, challenged by developers who subdivide the landscape and disrupt the historical timeline of our early agricultural past.

Of Fire & Ice: Rocks & stones in the Yankee landscape

Criss-crossing New England for 40 years while shooting annual reports and ad campaigns for Fortune 500 clients, I learned that New England is a land of intimate landscapes. Unlike the panoramic West, here you find your photos close at hand and underfoot.

My interest in “rocks in the landscape” goes back to my youth. Growing up in Gorham and Berlin in northern New Hampshire, I’d skip school to hike the Presidential Range through the White Mountains. After graduation I worked as a backpacker for the Appalachian Mountain Club and weather observer at the summit of Mt. Washington.

That’s where I taught myself photography—shooting the rocky headwall at Tuckerman’s Ravine, the Gulf of Slides, and Lion’s Head. I became intrigued by the abundant evidence of our geological history, passing glacial till, boulder fields, and gigantic out-of-place glacial erratics on my weekly trek up Mt. Washington to report to work at the weather station. With reportedly the worst weather in the world, the summit of Mt. Washington, even at a puny 6288’, is well above timberline, and tiny alpine trees and finally only rock fields decorate the mountain top.

When I left New Hampshire and moved to Connecticut in the ‘60s, I’d hike the nature trails, where I’d see remnants of early colonial settlements, stone walls outlining fields of the post-colonial farmers, the rebuilt walls of the later gentleman farmers, cellar holes and stone-faced root cellars, stone-surrounded graveyards, industrial factory foundations, millstones, waterwheels, stone bridges, dams, and water locks.

Beyond the city limits of Hartford, up and down the Connecticut River Valley and along the New England coast as far north as Maine, lies abundant evidence of the great turmoil 20-30,000 years ago when the Laurentide Ice Sheet invaded New England from central Canada, stripping away ancient soils and scouring the land down to bedrock. The immense power of this encroaching ice lifted billions of stone slabs, scattering them across the region.

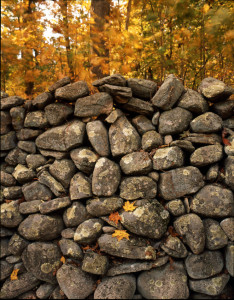

Five years ago when I began my Stone Wall project, I was drawn by the form, the quiet criss-crossing of piled stone against the context of surrounding woods and fields. The scurf of lichen against granite stone. Fiddleheads nestled within a niche of sun-baked rock. The puzzling presence of glacial erratics in an empty field.

When I come upon a stone wall, and bend to adjust my camera and focus my lens, I can’t help but feel the presence of the original hand that first stacked stone upon stone, maybe 200 or 300 years ago, I think of the generations of stewards and caretakers since who have mended the wall and kept Nature’s cruel intentions at bay. I examine the stones, dropped here 20,000-30,000 years ago by the roiling glacial turmoil of the last Ice Age. And I think of the hot furnace that forged these stones millions of years ago in the belly fires of Earth. By stopping here to tinker with my cameras on this sunny or moody day, I become part of this history, and connect to that long line of events.

At the time of the Civil War there were 240,000 miles of stone walls in New England, enough to get to the moon and beyond. But now the inventory of stone walls is fast diminishing, as are the farms themselves. Connecticut’s 360,000 acres of productive farmland contribute fresh food, scenic beauty and wildlife habitat, but the state is losing 9,000 acres of farmland to development every year. In the past 20 years alone we’ve lost 21% of our state’s farmland. Without vigorous public and private effort, at the current rate of loss, Connecticut will cease to have any significant tracts of farmland left by the middle of the century.

As the land is developed, we see the dismantling of its legacy of stone walls, and with it the loss of the irreplaceable gifts of the land. There is no other New England landform or icon to rival that of the much-beloved stone wall. Just try picturing New England without stone walls.

Connecting with Colonial farmers

As I stand in front of an old stone wall somewhere in Central Connecticut, up a side road away from cars and all the trappings of modern society, I feel myself being transported back 300 or more years. The stones were old, even then. Almost as old as time itself. I imagine a man, bent over the beginnings of a wall, stones scattered around him. A horse and a sledge behind him. He examines a stone, picks it up and carefully places it on the wall, working slowly, but steadily, working around the perimeter of a small field. His sweat, mingled with the stone imprints his DNA, his life, onto his labor, his wall. Three centuries later I am standing in exactly the same spot. I am transfixed, zen-like, contemplating the meaning of the stone wall’s existence. I wonder what his life was like. How did he ever survive. I live only by the grace of modern medicine. He didn’t have that. I think how fortunate I am. I look again at the wall and meditate on being alive.

As I work through this project, photographing old Yankee stone walls, I find myself becoming more and more enamored with individual stones and their placement within the artwork of the wall itself. Other details come into play that enhance the visual, the mystical experience of the wall. A garland of bittersweet flowing naturally over the stones. Fall foliage, a branch luminous in the rain, red and orange, contrasting the gray and green/yellow of stone and lichen. A leaf, bright yellow in a crevice, shouting out its color, “Here I am!” on a wall of greenish rock. Fog enveloping bare trees behind a wall, making the scene more mystical. An old barn. A rusted hulk of an old tractor. A field of yellowed grass…All speak their piece. To find all of these things, one has to stop. Move about on foot. Listen. Feel. Become one with where you are.

It doesn’t get easier—

As I work on our stone wall project, the pictures are becoming harder and harder to find. Why? Because I’ve gotten most of the obvious, expected images. Why? Because I have explored a lot of my environment already. What is left? Unique weather. Better light. Undiscovered walls. All of which are hard to find. But I keep at it. I drive farther. I look for fog, early and late light. I’m more discriminating. I study the walls more carefully. Details, angles, backgrounds are more important. Color is important. I go out when I probably shouldn’t bother, hoping for a magic moment. Sometimes it happens. I sometimes use strobe, even in daylight. I shoot at night. I add people to a few more stone wall images. I’m not done yet!

Connecticut may be one of the tiniest states in the union, but packed within its two hours north-to-south and two hours east-to-west, is a fascinating landscape with plenty to keep a photographer busy. And what’s caught my eye over the past year, has been miles and miles of Connecticut stone walls.

For 40 years while creating story-telling photographs for my corporate and institutional clients as I shot their annual reports and advertising campaigns, I often said I leave no stone unturned. But now, I’m actually shooting the stones and rocks themselves!

In every season, first light finds me traipsing through woods, or poised along the borders of a farmer’s field, sometimes eyeball to eyeball with a turkey hen or dairy cow. I plant my tripod, adjust the shutter speed, and recapture another piece of history, for most of these stone walls stand as evidence not only of Connecticut’s agrarian past, but also its geological roots.

To know New England well, one must know its stone walls. Forged at scorching temperatures deep within the Earth and brought to the region by huge glaciers, each stone is the result of both fire and ice. Today’s stone walls continue to be transformed largely by biological processes. Bacteria tarnish them. Lichens dissolve them. Vines penetrate and loosen their stones. Trees, blown down during hurricanes, knock large gaps in walls, as though taking bites of the earth. Left untended, every wall will come apart, tumble to the ground, disperse over acres of soil, and be buried by encroaching vegetation. Although inanimate, stone walls have an important story to tell. They give us a clock by which we can judge the passage of almost unimaginable time.

A selection of Jack’s stone wall prints are on exhibit until July 18 at the Celeste LeWitt Gallery at the UCONN Health Center in Farmington. To learn more about the fascinating story of New England’s stone walls, check out Stone by Stone by UCONN Geology Professor Robert Thorson.

To learn more about Jack’s stone wall project, visit his websites at www.stonewalljack.com and www.connecticutstockphotography.com or contact him at his studio/gallery: Jack McConnell, McConnell & McNamara, 182 Broad St. Wethersfield, CT 06109 860.563.6154, e: jack_mcconnell@msn.com