To see more stone wall photographs click on this link: NE stone walls

For anyone interested in the history and geology of stone walls, Jack recommends this excellent book:

Stone by Stone by UCONN Geology Professor Robert Thorson. Here are some notes from his book.

****************************************************************

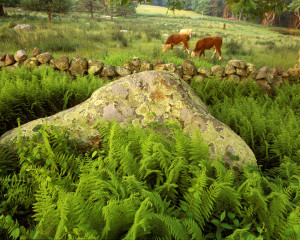

Nature is busy—over time and untended, stone walls revert to a playful splay of rock, more closely resembling the earlier tossed walls or rock piles. Stone walls provide a safe haven for woodland animals, keep the farmer’s stock from straying, and even act as an ecological barrier to the intrusion of plant species.

****************************************************************

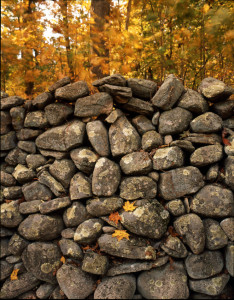

As farmers cleared forests and planted fields with seasonal crops, harsh winters would divulge a whole new harvest of rocks. Stone walls were often built thigh-high as farmers tossed the rocks aside that surfaced after the freezing and thawing action of New England winters.

This happened to coincide with the “Little Ice Age” and as farmers cleared the forests, there was initially plenty of wood for heating their homes, and creating fences. But after deforestation, the open fields became much more exposed to winter cold, causing it to freeze deeply, accelerating the process of frost heaving, in which the stones are lifted through the finer soil to the surface. When spring rains and snowmelt came, the water couldn’t infiltrate as easily as through the unfrozen, forested soil, forcing it to flow over the surface with corrosive force, removing the loam and concentrating the stone. And soon, the clearing of stones from pastures and fields became an annual chore for a generation.

****************************************************************

Early farmers used fences to pen animals for the strategic dropping of manure, and to separate livestock from crops. Subdivision of land within families added even more boundaries and fences. These fence lines became magnets for stone refuse that would otherwise have ended up in stone piles. Stones were often lugged to the side of the field by hand and tossed one upon the other. More commonly, a load of stone was skidded to the edge of the field on a wooden sled pulled by oxen. The large boulders were rolled into position; and smaller stones were tossed above and between them. As the stone accumulated, primitive “tossed” walls began to rise up out of the woods, replacing the lower tiers of wooden fences.

****************************************************************

Few stone walls were actually high enough to qualify as legal fences, but they were expedient boundary markers separating private lands, a kind of “no trespassing” sign. A few were ornamental in nature; but most served the useful purpose of being linear landfills, built to hold the waste stone that littered the farmer’s field. The height of most stone walls—thigh high—was governed more by the ergonomics of lifting and tossing stone than by the mandate of fencing. The simple, inward-slanting, internal structure of most walls was a “least-work” trade-off between the investment of energy required to build the wall and its long-term stability.

****************************************************************

To know New England well, one must know its stone walls. Forged at scorching temperatures deep within the Earth and brought to the region by huge glaciers, each stone is the result of both fire and ice. Today’s stone walls continue to be transformed largely by biological processes. Bacteria tarnish them. Lichens dissolve them. Vines penetrate and loosen their stones. Trees, blown down during hurricanes, knock large gaps in walls, as though taking bites of the earth. Left untended, every wall will come apart, tumble to the ground, disperse over acres of soil, and be buried by the encroaching vegetation. Although inanimate, stone walls have an important story to tell. They give us a clock by which we can judge the passage of almost unimaginable time.

****************************************************************

Stone walls not only transformed waste into something useful, they improved the local wildlife habitat with respect to diversity. Prior to wall construction, the dry-land habitats of cliffs and ledges were much more restricted in New England; animals and plants that had adapted to such terrain now had a greater chance to survive because stone walls and stone ledges offered similar opportunities.

****************************************************************

Stone walls stand as sentinel reminders of the agrarian period before New England became industrialized.

****************************************************************

Gentlemen farmers of the 19th and 20th centuries often laid stone walls at a higher height than the original tossed walls, or topped them with wooden fences to mark their boundary lines.

****************************************************************

****************************************************************